Repair work to Telekom Malaysia’s damaged Cahaya Malaysia submarine cable that caused Internet speeds to slow region-wide begins today, and we thought it would be a good time to look into what these cables are; or rather why they keep getting damaged and why it takes so long to get around to repairing them. The work on the cables is expected to be completed by the end of the month, which means our internet speeds should recover soon enough.

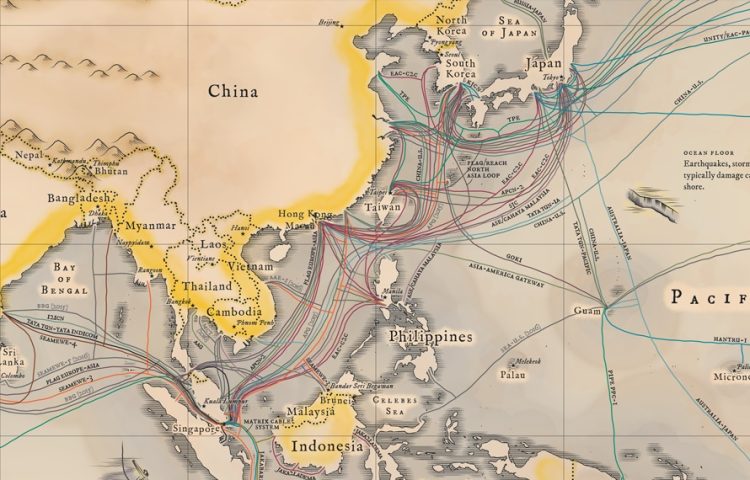

The globe is crossed by thousands of kilometres (Cahaya Malaysia spans approximately 7,800km) of undersea cables that carry the internet from one place to another. They are usually laid in groups, mainly as a redundancy precaution; but also to cope with the massive amount of traffic that passes through them. Practically all of the world’s internet passes through these submarine communications cables.

(Video: Vox Media)

It is for this reason that the cables themselves are mostly composed of protective materials. In general, the cables feature seven layers of what is effectively armour for the soft optical fibres on the inside. The layers include steel cabling for strength, an aluminium water barrier, and a layer of petroleum jelly to keep the water out.

As it is plain to see, submarine cables are incredibly difficult to damage; yet, damage does happen. Most of the damage happens close to shore, at depths of less than 150m. Contrary to popular belief, natural disasters like undersea earthquakes rarely cause any disruption. Evidence of this can be seen from the fact that cables traveling out of Southeast Asia must pass through an area geologists call the Ring of Fire: a region with enough earthquakes and active volcanoes to make you wonder who decided that this was a good place to live.

Damage, more often than not, comes from humans. This happens in the form of anchors or fishing nets being dragged along the ocean floor and getting caught on the cables. In fact, anchors are responsible about a quarter for all submarine cable damage in the world. Industry experts refer to this as ‘external aggression’.

That being said, cables have also been known to suffer damage from curious sharks – who bite the strange object in an effort to figure out what it is.

Fortunately for us, Cahaya Malaysia is part of the Asia Submarine-Cable Express (ASE); which was built by a consortium of telcos from Southeast Asia. When the cables were damaged, TM simply started routing traffic through its partners’ cables to keep the connection stable. Of course, this had the side effect of increasing the load of the remaining cables, which is why your internet connection is slow and not completely cut off. It is also why the rest of the region is experiencing the same problem.

Fixing the break requires engineers to first figure out where the break has occurred. This takes a lot less time than people think it does, thanks to everything effectively working at the speed of light. Essentially, engineers send a light pulse down the fibre-optic cable to check if it’s still working. If it is, the pulse goes all the way to the end of the cable; you know, like it’s supposed to. If there is a break, the light gets reflected back towards the source. From there, it’s a matter of calculating how long it took for the pulse to return to figure out where the problem is. Modern systems can make the necessary calculations in about 20ms.

Actually fixing the cable is just a matter of hauling it back to the surface and splicing a new piece of cable back in. This involves specialised grappling hooks that are lowered into the ocean, although engineers may occasionally have access to submersible drones if the breakage happens in shallow water. Getting to the location could take days, or even weeks if there is bad weather; this is the main reason why repairs take that long to complete.

TM has not revealed the cause of the recent damage, and telcos are not in the business of telling people what caused the most recent damage. That being said, Cahaya Malaysia runs from Singapore to Japan, a massive distance where anything could have happened along the way. Although in this case, “anything” would most likely be a fisherman trying to make a living; or a shark wondering what this giant black noodle tastes like.

[Source: Telekom Malaysia, Telegeography]