I’ll be the first to admit: I’m not a huge Dota 2 fan. As an FPS nut, I was hugely invested into Counter-Strike: Global Offensive, where I used to play competitively online with a colleague of mine (he was ranked Legendary Eagle Master, and my “career high” was Legendary Eagle). Then he left, and I no longer had a friend who was at my level in CS:GO.

After many failed attempts at making my colleagues better at CS:GO, they turned the tables around and began tempting me about ways Dota 2 is more fun. Given that my last brush with the game was when it was still known as DotA, playing in dingy neighbourhood cyber cafes with secondary school students playing truant, I wasn’t so easily convinced.

But this is the heart of a movement that has got the world turning its attention to what is now universally known as “e-sports”. Dizzying amounts of money are being poured in from all sides, with prize money that usually eclipses that of traditional sports. This is a global phenomenon that is here to stay, and here in Malaysia especially, the e-sports scene booming.

Major tournaments have taken place in Malaysia over the past year, and local telcos especially are leveraging on their fast and stable LTE networks to appeal to gamers for streaming live matches. 2017 will be more of the same, with Digi leading the way as the sponsors of the biggest Dota 2 tournament in Malaysia so far, the ESL One Genting in January.

Malaysian representatives at ESL One Genting, WG.Unity

Malaysian representatives at ESL One Genting, WG.Unity

Professionally, I was intrigued. So for the past few months, I have been dabbling with the game alongside colleagues who are more experienced in the game.

After about 250-odd hours poured into the game (I know, that’s not much by any means), here’s what I think: I hate this game. I genuinely despise so many aspects of the game (none more so than how toxic the community can be – more on that later), but worst of all… I hate the way I can’t get away from not playing it.

Like all other addictive games, Dota 2 pulls you in by giving this false impression of how easy it is to play. Choose a hero, use its unique skills to kill other heroes, destroy the opponent’s base, and win. Initially, I was playing with colleagues who have been playing for years, so it was easy to win matches at that point (because my low level brought the average matchmaking difficulty way down), and it let me observe play styles of good players. That’s how my first 50 or so hours went.

Then things got serious. I began playing on my own, solo-queueing late into the night, fixated on improving my ability to play as Sven the Rogue Knight. It was around then that I first encountered the toxic nature of the game’s community. Team fights that go awry in the lower skill level matches tend to be followed by a massive blame game over whose fault it was – and they get nasty very quickly.

The topic of a toxic community remained a constant theme in my time playing the game. I’ve been in matches where teammates hurl walls of text at each other, filled with words that would make the ladies blush. Or the times when the opponents gloat unnecessarily (“gg ez” and its many variations). And don’t get me started with the occasional a****** who throws the game because there was “no support”.

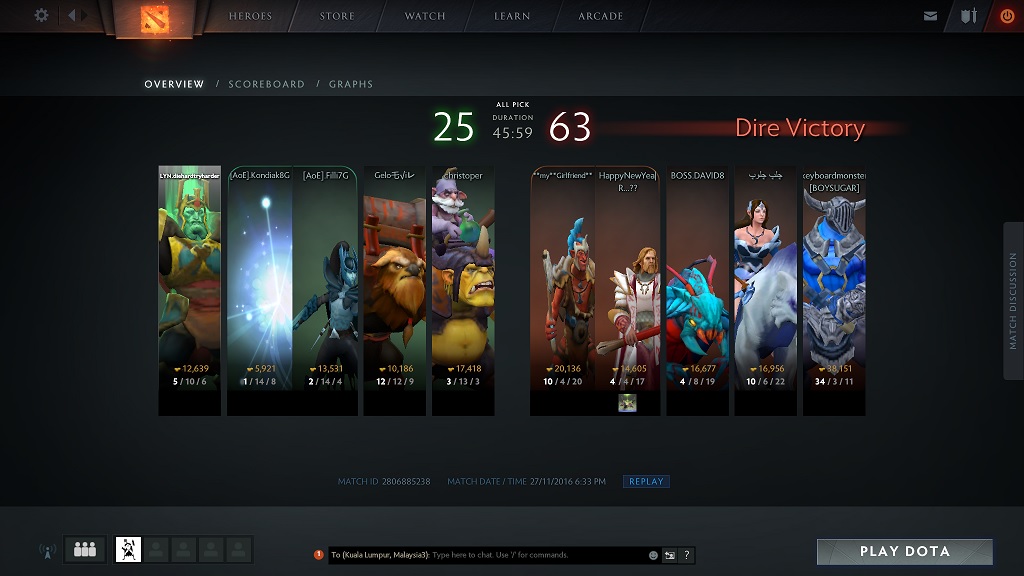

Because each match lasts an average of 45 minutes or more, players are invested into the game and winning a match (or at least making it a close fight) becomes important. And because of that, some players simply cannot control their emotions, which eventually made the game not as fun as it should be for me.

Don’t get me wrong, I’ve seen similarly toxic players in CS:GO as well. But CS:GO is a skill-based game where one exceptional player can take down the entire team in some situations. Dota 2’s mechanics means teamwork is essential to winning the game; so having a toxic teammate means 45 minutes or more wasted – and you don’t even get to enjoy playing.

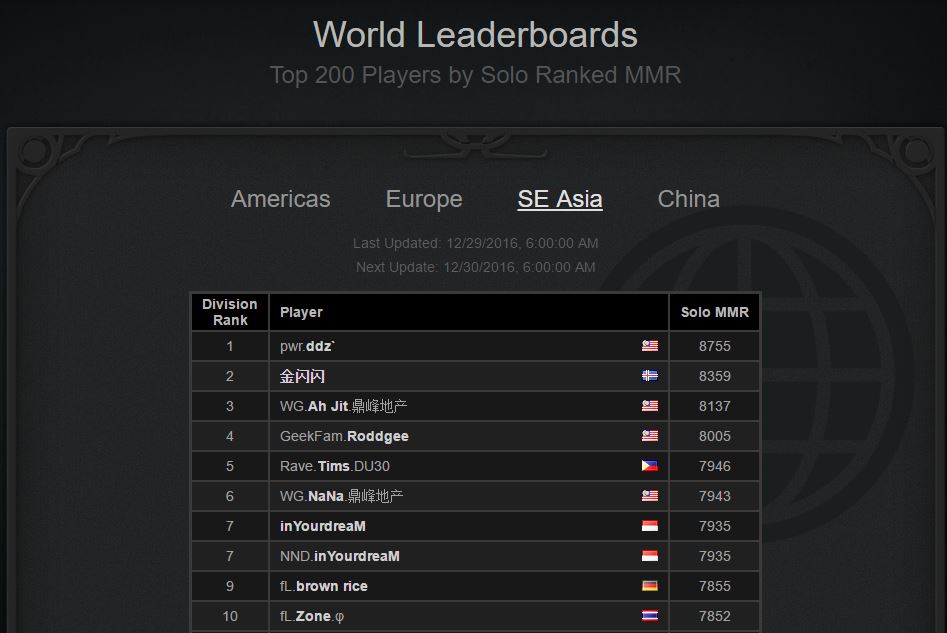

But I persevered. I’d already gone past the 100-hour mark, and toying with the idea of ranked matches and understanding how MMR works (and how flawed it is). But first, I was experimenting with other heroes, and trying to understand the roles of each hero I play. It was complex stuff, and more so when you need to consider what heroes my team was up against; this level of thinking is simply not present in CS:GO, which has a more linear (though arguably just as exciting) approach.

This aspect of the game got me even more hooked. I began to understand the depth behind terms such as “creep equilibrium”, and how to counter-pick on enemy heroes and disabling them in team fights. I read up and watched videos on heroes that I liked, and how to suit recommended game styles that match my own. I even got into an unusually intellectual discussion with my colleagues on which attribute the Phantom Assassin would benefit more from (base damage or attack speed), and why (personally, attack speed).

However, the honeymoon period ended at around the 200-hour mark for me. I’d begun playing ranked matches almost exclusively, and because I’d done that so early in my “career” with limited game sense, after 10 matches my solo MMR was revealed to be a fraction above 1k, putting me in a very difficult spot. Matches were short, and the trash talk was constant. At this level, “solo” players or those who refuse to play as a team were everywhere; these same players would then proceed to completely eviscerate teammates for “our lack of support”.

It didn’t help either that no matter how well (or how badly) you play, everyone earns or loses the same MMR per game. At just 25 points, moving up and above the lower-level players is a massive grind – it is completely inexplicable for me that you should earn the same points when you win regardless of how you contributed to the match.

Eventually the inevitable happened: I became jaded with the game. The excitement of trying out different hero builds did not outweigh the toxic environment I was experiencing (even in unranked matches). Most players were unforgiving, and eventually they got to me.

I remember that match as if it just happened. No one in my team had played particularly badly in the early game – the opponents simply had a more balanced team (which is rare in low MMR matches). That, coupled with the poor communications from my teammates (who were all from a non-English speaking country), meant horrible coordination in team fights, and by mid game, I was on the receiving end of some serious and constant abuse. It was obvious from the match stats that I wasn’t the reason why we lost, but it didn’t matter. I uninstalled Dota 2 from my laptop, telling myself it wasn’t worth the abuse. I was done.

I was happier after that. I ate better, I slept a lot more. I went out and saw more friends. Did more work. I missed playing the game, for sure, but I found myself having more time to do stuff.

And then came the 7.00 update, and with it the massive visual overhaul. The sheer number of changes was almost like someone hit the reset button – suddenly it was almost like everyone had to start over. My colleagues raved about how everything just looked so much better, and like an addict suffering from withdrawals, I caved in.

I downloaded and reinstalled Dota 2. I read up on the changes, and about the new hero, the Monkey King. The Talent Tree, and how dramatically it can change the game. I’ll admit: it made me genuinely excited about playing the game again. And played I did, in our Facebook Live session for our readers to see.

As a math geek, the addition of the Talent Tree was the main reason why I got back into the game. The boost a hero gets at important moments of the game means chances of the game turning on its head was greater, which made things more exciting. It pushed players to think on their toes whether it was more advantageous to add 200 mana or 6 strength (i.e. one extra stun/spell vs a higher base damage). It made an already dynamic game even more unpredictable; just imagine what it was like for those who played in the Malaysian qualifiers for ESL One Genting, which took place right when the 7.00 update happened.

So here I am, hopelessly fixated on a game I know will frustrate me. And I know that eventually, I will reach a point where I will question this decision to immerse myself in this game once more. But I’m a bit busy right now; I’ll ask myself that after I’m done analysing the Monkey King nerf in the 7.01 update.

(Featured image source: Goliath)

Disclosure: This article was sponsored by Digi. Digi is an official sponsor of the ESL One Genting tournament.