Digital textbooks are being implemented in Malaysian schools from this year onward. It effectively means that students will be able to eventually opt out of carrying heavy physical books, and simply accessing everything from the Internet. On the surface, this looks like a great step towards leveraging modern technology for education.

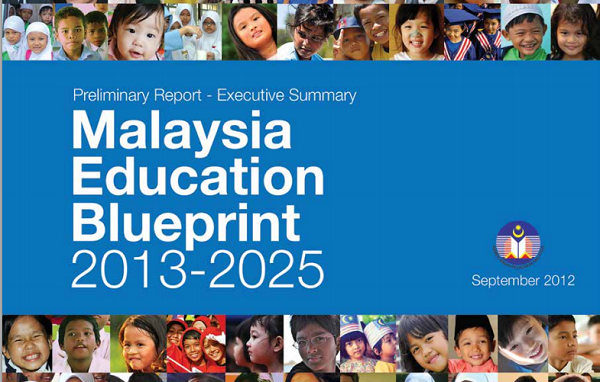

All this is part of the 13-year Malaysia Education Blueprint (Pelan Pembangunan Pendidikan Malaysia (PPPM)). The first step is to make current textbooks available for viewing over 1BestariNet, and that is already underway with 313 textbooks uploaded. The second wave, due to happen from 2016 until 2020, will see updated textbooks with interactive elements.

This move towards a more connected education system works, if students are allowed constant access to tablets or computers, something that the Education Minister II Datuk Seri Idris Jusoh says will happen eventually. He also says that students will be allowed to bring their own devices to the classroom. There are only two problems with this scenario, both involve access to the technology.

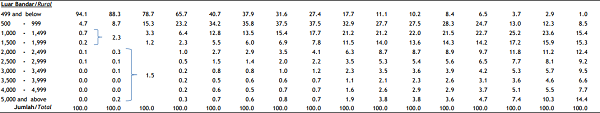

Firstly, is a matter of the digital divide. Not everyone has access to computers or tablets. Income inequality between urban and rural communities results in less technology going around places that are not massive cities. For instance, statistics for 2012 show that the average income for urban areas is RM5,742 while rural areas average about RM3,080. That looks like a great number, but averages are a bad indication of how things are.

The Economic Planning Unit has a better breakdown of income according to states. While the average income for rural areas looks high, the median number looks a little different. In fact, 15.4% earn between RM1,000 and RM1,499 and 15.3% earn between RM1,500 and RM1,999. Which leaves about 1/3 of the rural population earning far less than the average income.

That raises the question then, how will these people afford devices to access the digital content? Tablets are not cheap. Even an off brand version from the backwaters of China cost about RM399. That’s just one device; consider that families are, on average, about 4.6 people. Which means between two and three children per family. Which means between two and three tablets that need to be purchased to get the most out of schools.

Naturally, we could attempt to shift that problem to the government. After all, this is their idea. Plus, Malaysians love their subsidies.

Of course, the government cannot only provide devices to rural areas; lower income groups also exist in urban areas. So it’s safe to say that we might as well consider the need to provide devices for everyone. It’s not easy to find numbers on Malaysian student enrolment, but Wikipedia pegs it at about 5.5 million. Which would result in an almost obscene cost to the education ministry – a ministry that already receives the largest national budget percentage not just in Malaysia, but in the region.

Naturally, the challenge is not only providing students with devices to access the all-digital content that is set to appear in 2025, but also providing technical support for schools in order to ensure lessons continue uninterrupted.

To be fair, several pilot projects are already being implemented with Yes4G already providing Internet connectivity to some 10,000 primary and secondary schools nationwide. Similarly, cost-saving Google Chromebooks are being deployed in selected schools.

The other issue with using electronics in class is a matter of how effective it really is. Some will be familiar with the Khan Academy, which already provides a large number of videos teaching a variety of subjects. It is mainly about the American syllabus, but worth looking at for extra lessons.

Khan is highly regarded as an educational tool, with some American schools officially adopting it to augment lessons. If our future digital textbooks follow the same methodology and style, we could be in good hands. It wouldn’t be too hard to copy it either, seeing that Khan is free to use and access.

However, this video from Australian based Veritasium points out the potential weaknesses in that sort of approach to educational videos. Essentially, students are very likely to zone out and stop listening to content if it is not presented in the right way.

This is compounded by the fact that the Ministry will eventually allow students to bring their own tablets to classrooms. How does anyone intend to keep students focussed on the teacher while they have access to the entire Internet?

However, moving to a completely digital education system is inevitable. We cannot avoid it simply because there will be issues in deploying the scheme. Fortunately, the plan extends for 13 years, which allows for plenty of time to plan for any eventual shortcomings.

Nobody will argue that there is a need for improvement in the national education system (although this applies everywhere) and creating a plan for reaching the future is more than a necessity. That being said, it would be nice to have a more information on how we intend to achieve this. There is a UNESCO summary which elegantly sets out the strengths and weaknesses of the Malaysian education system from a more neutral standpoint.

More importantly, it provides extra insight into what the PPPM is about in a manner that is easier to digest. Interestingly enough, this summary mentions that the upgrading of school infrastructure to meet basic requirements is set to begin in 2015 – starting with Sabah and Sarawak. Not the usual starting point, but also the two states that need the most work.

Additionally, it outlines the government’s approach to addressing the digital divide. Supposedly by experimenting with alternatives for ICT facilities like lending notebooks for libraries and computers-on-wheels. Ideally, this reduces the number of devices that will have to be provided to students. Student information could easily be stored in the cloud, which would make it not only easier to share devices with other students, but also allow parents to track the development of their children.

Malaysia may not be able to fully deploy digital textbooks yet, but the future is not entirely bleak. There is some semblance of a plan, despite it not being fully detailed to the public yet.

Perhaps a greater concern is whether our next generation will be able to take advantage of the tools provide to them.

Follow us on Instagram, Facebook, Twitter or Telegram for more updates and breaking news.